Seth Nicemail – conceptual correspondence art

0

0

For many years (since 2009), I have been actively engaged in artistic verbal communication on social media. I apply this one-to-many approach in a modified way to the physical world through mail art.

In conceptual correspondence art, the recipients may be unaware of each other, yet they are interconnected through the underlying artistic concept. They become part of the artwork, even without knowledge of the concept itself.

While each recipient of a piece may choose to appreciate it, ignore it, or discard it, a project is truly complete when – though this remains hypothetical – all recipients, including the artist, come together to reveal the bigger picture as a community.

Mail art projects

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Exhibitions

CARTES POSTALES et MAIL-ART

Paris, France

Group show

#8 item 8/15

Change / Kunstraum Reuter

Berlin, Germany

Group show

#6 item 4/15

Flaschenpost / WERK 2

Group show

#5 item 5/49

Kreiseln / Kunstverein

Group show

#5 item 3/49

Incoming mail art

Impressive mail art received from across the globe: an inspiring mix of creative techniques and compelling ideas.

Rosemarie Drews

Rosemarie Drews is a German artist and participated in some mail art calls I came across. The beautiful piece titled "Kreisel" clearly comes from the same series as her artwork shown at Kunstverein Eislingen.

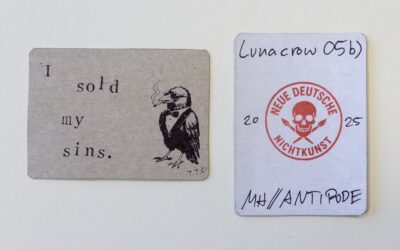

MH//ANTIPODE

MH//ANTIPODE from Germany sent his artwork in a securely sealed envelope that took some effort to open. It was worth it: I like the cards saying "I sold my sins" and "I collect what you abandon", as well as the mysterious sheet of abstract art. Is that biker smoking a...

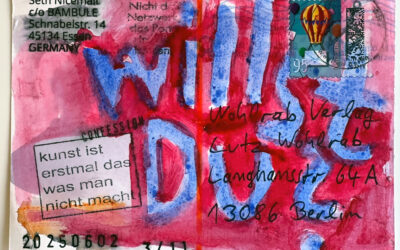

Lutz Wohlrab

Berlin-based Lutz Wohlrab has been a well-known (mail) artist, collector and publisher for about 40 years. He recycled my postcard from my Confession project in an exemplary way. Well, that’s us Germans. 😉

The history of the mail art movement

The Mail Art movement, also known as Correspondence Art or Postal Art, is an artistic practice that began in the early 1960s. It is based on the exchange of artworks through the postal system and sees itself as a counter-movement to the established art world. The core idea: anyone can be an artist, and art should circulate directly and uncensored between people, outside the commercial art market.

The origins of the movement can be traced back to American artist Ray Johnson. Johnson, an early representative of Pop Art and founder of the “New York Correspondence School,” began in the 1950s to send small collages, drawings, and texts to friends, acquaintances, and fellow artists via mail. These sent works were not static objects but were meant to be modified, copied, or forwarded to others. This created a circulating network of communication and creative exchange.

In the 1970s, Johnson’s initial impulse developed into an international network of artists, shaped by the expansion of the Mail Art principle. The movement gained considerable traction especially in Europe, Latin America, and Japan. Key figures in its development included Klaus Groh (Germany), Ulises Carrión (Mexico/Netherlands), Anna Banana (Canada), and Guglielmo Achille Cavellini (Italy). Together, they contributed to the formation of a global communication network that enabled artistic exchange regardless of cultural, political, or economic boundaries.

Mail Art as a medium is remarkably open. Typical forms include postcards, envelopes, rubber stamp art, collages, drawings, photocopies, or small objects – as long as they can be sent by post. The emphasis is less on the finished artwork and more on the process of sharing, interaction, and networking. A key motto of the movement was: “No jury, no fee, no return” – a manifesto against exclusivity and commercialization.

With the rise of digital communication in the 1990s, traditional Mail Art lost some of its momentum. However, its core principles live on – whether in digital formats, social networks, or in contemporary projects that continue the idea of artistic exchange. Some artists today deliberately return to analog postal art to counter the speed and ephemerality of digital media.

Mail Art is thus more than just an artistic genre, it is a social, political, and aesthetic statement. It raises questions about authorship, participation, public space, and the boundaries of the art system. Its influence extends into today’s practices of networked art, open-source culture, and community-based art projects. The movement has shown that art does not have to be confined to museums and galleries: it can take place in mailboxes, on envelopes, and in everyday communication.